Scholarship

The Shepherd’s Philosophy: Pastoral and The Good Life

Thursday, April 28th, 1983

An Address to Philosophy 152: Theories of the Good Life

Claremont McKenna College

April 28 1983

I want to talk about this week’s topic–The Good Life as Living in the Country–by loosely braiding three strands of material into a single line of argument. These strands consist of your assigned readings by Carolyn Lewis and Scott and Helen Nearing, a discussion of the pastoral tradition in literature, and an account of some of my own experiences with living in the country for the better part of nine years.

The idea that the Good Life is to be found outside the limits of civilization in a rural, natural setting is as old and as widespread as civilization itself–a word whose root signifies the culture of cities. Urban people have often reacted to the conflicts and tensions of their existence with the wholescale rejection of their artificial environments and with affirmations of what they imagine to be the simple, happy lives of those who live in the country. This attitude has been dubbed “primitivism” by historians of philosophy, who have discovered its traces in some of the earliest Sumerian and Babylonian texts.

Primitivism has always been especially popular among writers–poets, dramatists, essayists, novelists. Their utterances of love of nature and hatred of the city have constituted a distinct literary genus called pastoral or bucolic–after the shepherd or cowherd whose occupations seem to embody the primitivist ideals of simplicity, unpossessiveness, rapport with nature, and the leisure for erotic, artistic and contemplative pursuits. Some pastoralists assert the theory of the Good Life in the country from the heart; others do so primarily to display their ability with words.

One can see evidence of the breadth and self-consciousness of this pastoral tradition in the way each chapter of the Nearings’ book begins with numerous epigraphs from sources ranging from ancient Chinese proverbs to Shakespeare and Thoreau. These epigraphs indicate that much of what follows has been said many times before and for that very reason bears repeating. The pastoral theory of the good life in nature and of the corruption of civilization dominates the Bible. We find it also in Homer and Hesiod–who project visions of the Golden Age before cities were founded; in the Phaedrus–where Plato paints an idyllic scene of erotic philosophizing outside the city walls; and in the Bucolics and Georgics of Vergil”which praise the quality of life far from the seat of Empire.

(more…)

Youth Against Age–Chapter 5

Saturday, March 21st, 1981

5

The Backstretched Connexion:

Youth and Age

in The Shepheardes Calender

This chapter proposes an interpretation of The Shepheardes Calender which places the debate of youth and age at the work’s core. Spenser used both the thematic content and the formal structure of this minor bucolic convention as the central shaping principle of his major pastoral work. Such emphasis was particularly appropriate, first because pastoral’s rural settings on the periphery of civilization correspond to the peripheral states of the human life cycle, and second, because pastoral’s projection of dual worlds inspires debate-like comparisons of perception and judgment.

But Spenser did not simply reprocess these essential elements of the pastoral tradition. Rather he modified and enriched his conventional models by disclosing the debate of youth and age through the viewpoint of a narrative persona, a viewpoint which shifts in the course of the poem from identification with youth to identification with age. That is to say, Spenser used the pastoral debate of youth and age as a means by which to externalize the inner conflicts of past and future, of regression and maturation, endemic to adolescence. By patterning his series of eclogues with a phased succession of such debates, Spenser allowed the reader to participate in the reversal of perspective that constitutes the subjective transformation of boy into man. Moving from premises about the psychology of pastoral and about the philosophy of debate laid down previously, this chapter arrives at the conclusion that The Shepheardes Calender–a product of its author’s youth and addressed to youthful readers-has as its deepest unifying subject the life stage of youth itself. (more…)

Erik Erikson correspondence

Monday, October 20th, 1980Dessert for the Academic Gourmet

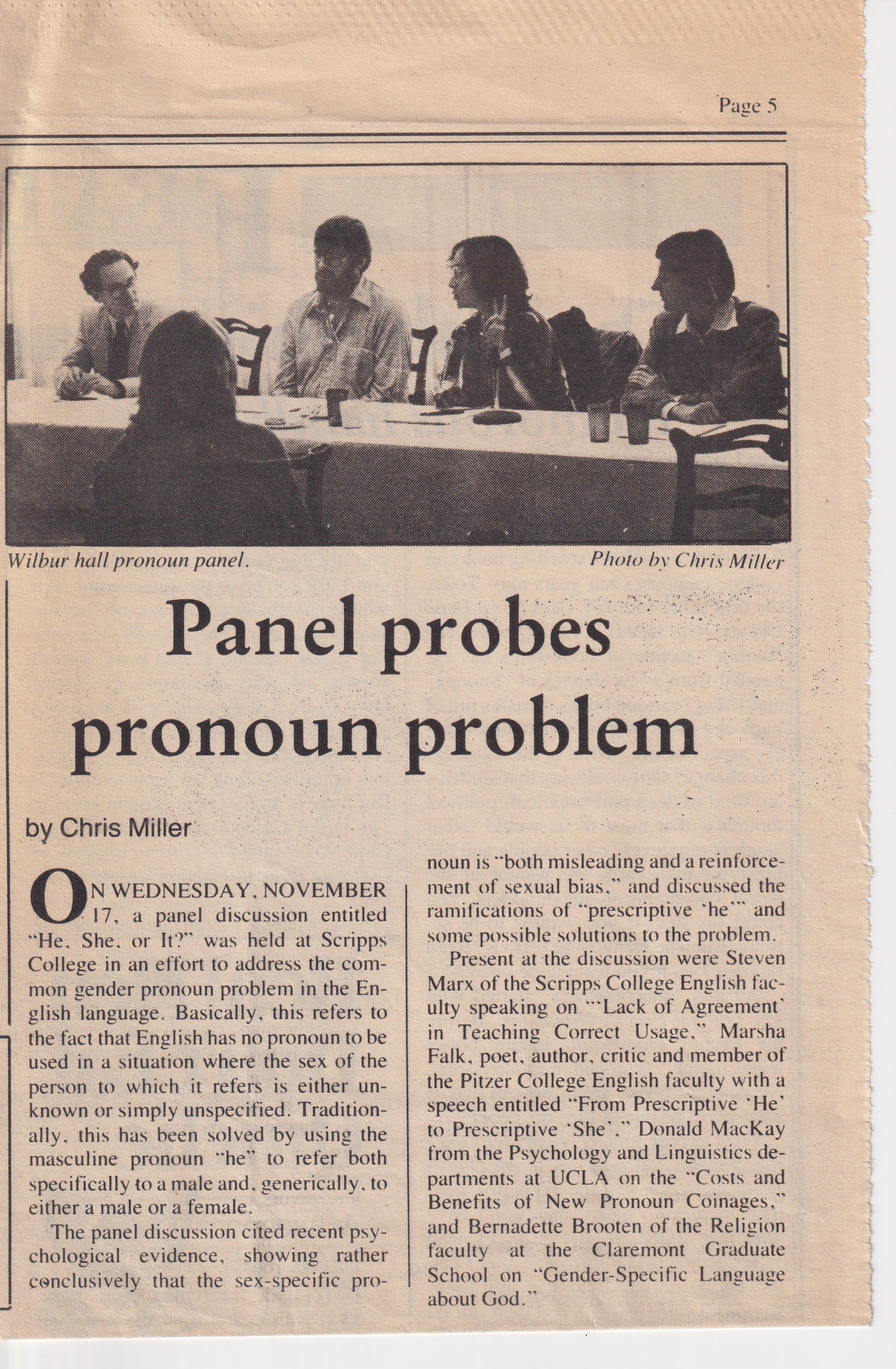

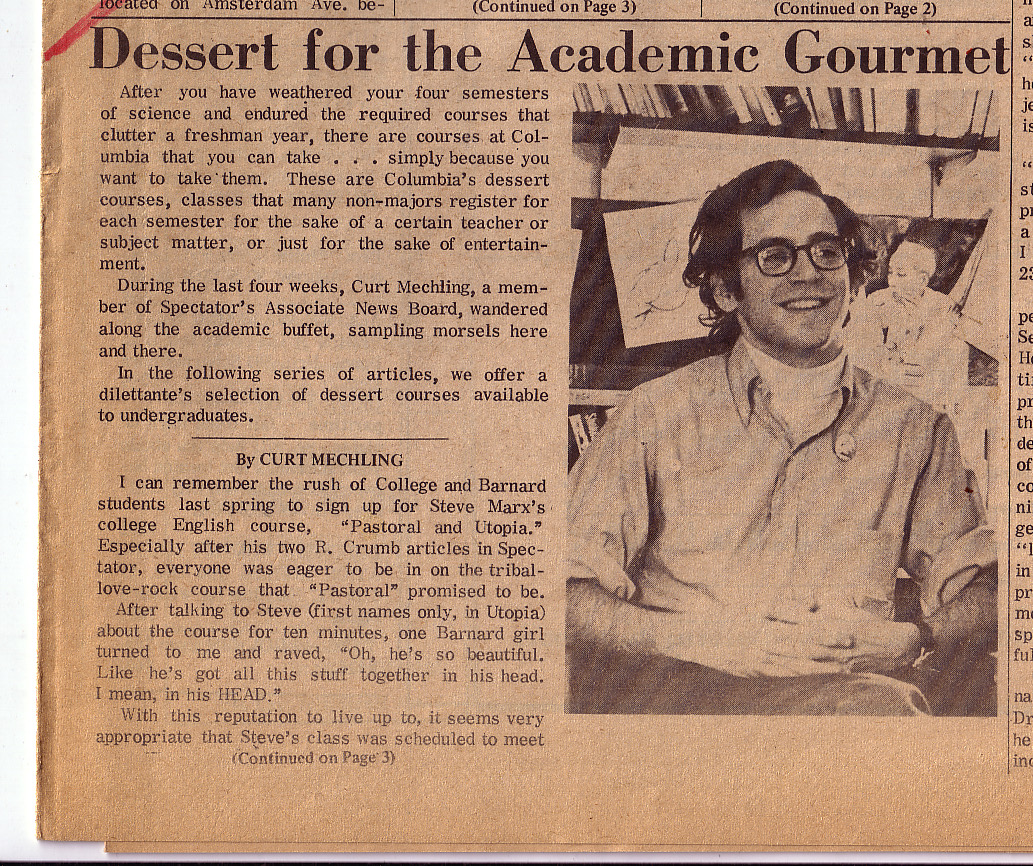

Thursday, December 11th, 1969R. Crumb: The Sacred and the Profane

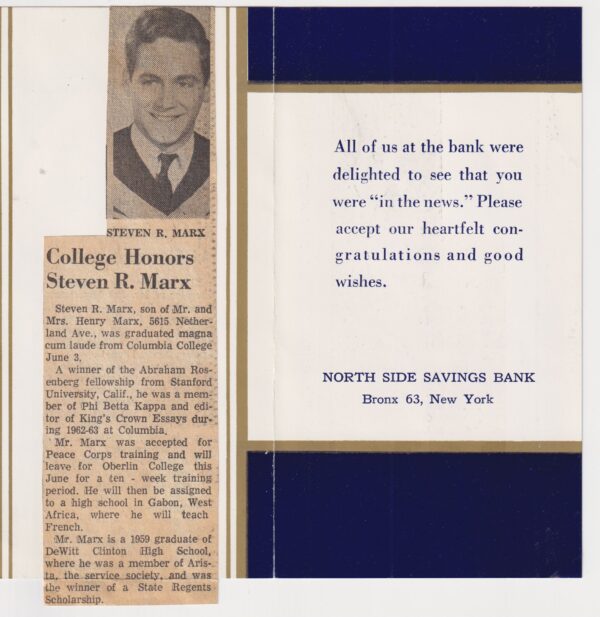

Thursday, March 27th, 1969We read about you in the news!

Thursday, June 20th, 1963

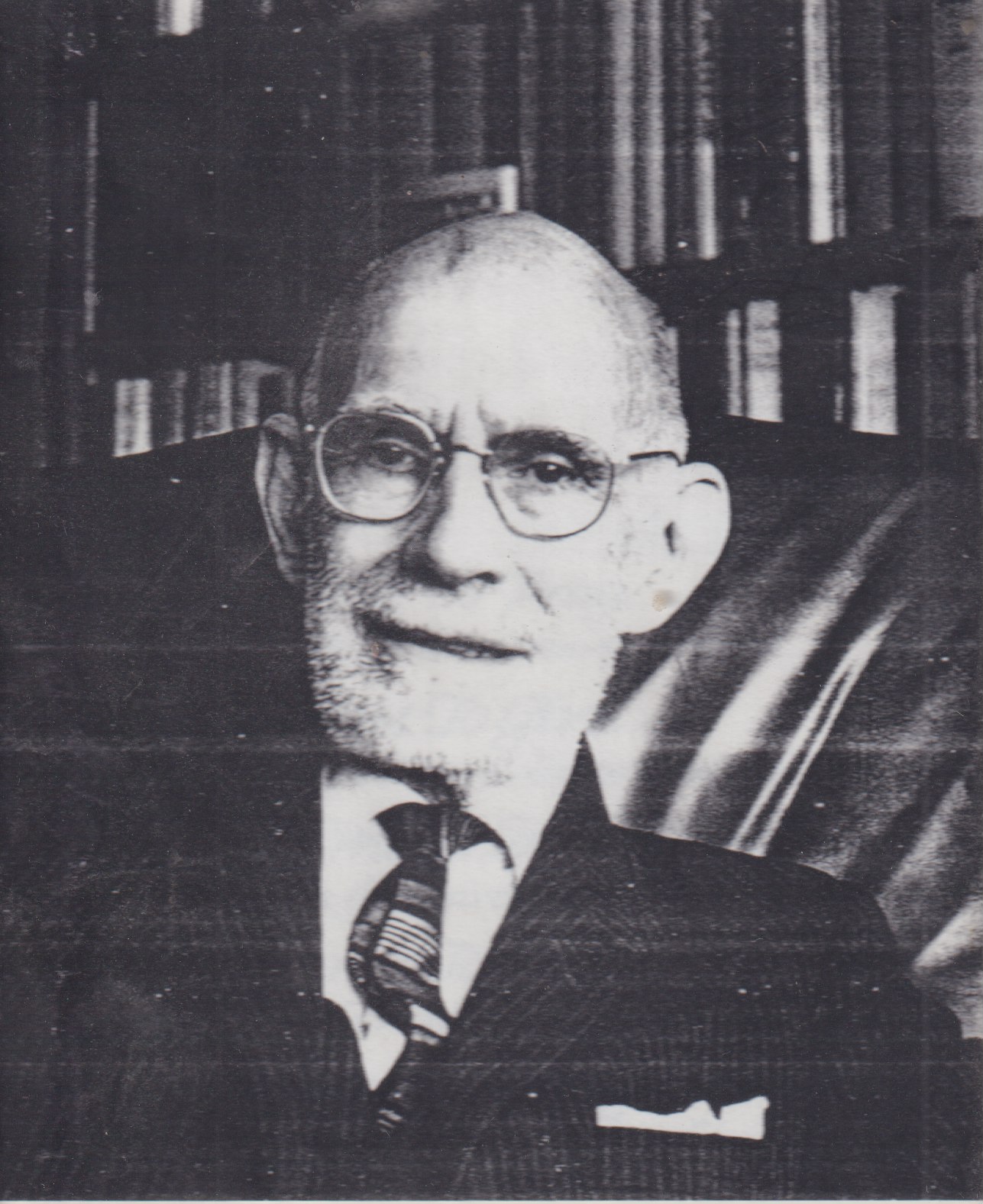

Morton Smith (1915-1991)

Saturday, May 5th, 1962I took his course in Ancient History at Columbia during my sophomore year 1960-61. It was incredibly rigorous and I loved every minute of it, especially filling in hundreds of locations of ancient sites on the base maps he had us buy, assisted with the required text of the Grosser Historischer Welt Atlas.

Deeply curious about the explicit homosexuality I read about in Plato’s Symposium in Freshman Humanities, I decided to write a research paper on this topic in other Greek classics and found that indeed the “love that could not be spoken” in 1959 was central to the exclusive culture of classical philosophers–not because I felt attracted to it but because it violated so many of the norms I’d grown up with.

The paper was returned with one of his rare high grades and with a surprising invitation to take a job as his reader for the same class during the following year, a job that involved meticulous correction of the maps and other objective parts of his tests.

I’m not sure whether it was during that junior year or during the following senior year that he also invited me to become his research assistant. Having learned about his exalted and frightening reputation (see the article below), I was immensely flattered and ended up spending several evening hours a week in his cramped apartment–every wall in it stuffed with books floor to ceiling–at close quarters, following his instructions to find key words in the thousands of note cards he was churning out next to me, write them in the upper right corner of each card and file them in the banks of oak drawers that could be moved around in the tiny spaces left on his floor. I knew that most of the material had to do with obscure early Christian sects and texts, but had minimal understanding of what they were about.

Sometimes he would take a break for supper, which invariably was apple sauce on toast. On one of those occasions, he invited me to join him in his bedroom, sitting on the bed which extended from one wall of books to another. After a little bit of small talk, he asked me if I liked opera, which I did, especially up in the affordable seats near the ceiling of the old Met on dates with one of the girls I was in love with during those years. Then he asked if I would like to join him at a performance of La Traviata on Saturday night. Suddenly I got the picture. Why select me to be his grader and invite me into such close contact when there was no chance I’d ever have the scholarly focus required of a real protege? But I wasnt shocked or offended, just a little regretful to turn down an offer which I sensed left him more exposed than I ever thought possible. We returned to work, but I dont think he continued scheduling me to come back.

One of the things I remember still was his fierce determination to debunk the historicity of the narratives of the New Testament, especially the stories of miracles. After I returned to teach at Columbia in the late sixties, I had no contact with him, and while teaching the Gospel texts in Humanities class, found myself enthralled by their stories of a charismatic leader inspiring faith in a growing community of dissident followers. On occasion and appropriately medicated, I saw myself playing that role. But many years later, while working on my book on Shakespeare and the Bible, I found myself drawn back to Smith’s perspective, which I detected being foreshadowed in the texts of many of the plays.

gospel-secrets-biblical-controversies-morton-smith